by Corinne Ramey, reporter for the Wall Street Journal

by Corinne Ramey, reporter for the Wall Street Journal

August 9, 2016 – 5:30 a.m. ET

January deadline looms for compliance with new legislation meant to speed up the pre-trial process

A massive overhaul of New Jersey’s bail system aimed at unclogging county jails and courts is spreading fiscal angst across the state.

January is the deadline for counties to comply with rules designed to speed up pretrial procedures and nearly eliminate money bail. The requirements stem from legislation signed in August 2014 by Gov. Chris Christie and a state constitutional amendment approved by voters several months later. They have been heralded by politicians, advocates and other officials who say the current system is inefficient, unsafe and unfair.

But as the deadline approaches, many county executives say they are struggling to comply and that the new rules amount to an unfunded mandate that may require cutting services or raising taxes.

“There are some significant upfront costs we’re looking at,” said John Donnadio, executive director of the New Jersey Association of Counties, which represents the state’s 21 counties. The association estimates complying with the new rules will cost the counties $45 million in startup costs.

Among the key changes: Whether a defendant waits for trial in jail will no longer be determined by whether he can pay bail, but rather by how risky it would be to release him. Also, courts must meet tighter deadlines for getting a defendant to trial.

To meet the new requirements, counties are having to hire new staff and keep court facilities open on weekends, Mr. Donnadio said. They are also purchasing new technologies like videoconferencing systems for court appearances and electronic fingerprinting systems.

A spokesman for Mr. Christie, a Republican, pointed to the governor’s previous remarks in which he has spoken of the monetary costs of holding defendants in jail and the human costs of breaking up families when one member is incarcerated. In June, Mr. Christie issued an executive order directing the acting attorney general to study implementation costs.

A spokesman for Mr. Christie, a Republican, pointed to the governor’s previous remarks in which he has spoken of the monetary costs of holding defendants in jail and the human costs of breaking up families when one member is incarcerated. In June, Mr. Christie issued an executive order directing the acting attorney general to study implementation costs.

Money bail is viewed as a deposit to ensure a defendant shows up for court and is widely used nationwide. Some critics say it unfairly penalizes poor people who don’t pose a threat and allows dangerous defendants with means to go free.

New Jersey’s new rules appear to hit a political sweet spot—liberals tout the benefits for poor and minority defendants and conservatives emphasize public safety and the savings of avoiding unnecessary jailing.

Under the new system, judges use a tool called a risk assessment to help decide whether to hold a defendant in jail. This takes into account various factors, such as prior convictions, whether the crime allegedly committed was violent and if the defendant has missed prior court dates.

Under the new system, judges use a tool called a risk assessment to help decide whether to hold a defendant in jail. This takes into account various factors, such as prior convictions, whether the crime allegedly committed was violent and if the defendant has missed prior court dates.

Those deemed to be dangerous or unlikely to show up to court will be held without bail, and most others will be monitored as they await trial at home. A small number of defendants could be assigned bail if the judge determines that money bail is the only way to ensure they make court dates.

Additionally, a defendant must appear in court within 48 hours of going to jail. For those held in jail, the rules lay out so-called “speedy trial” conditions, setting specific amounts of time by which certain hearings must be held.

Bruce Bergen, freeholder chairman in the County of Union, said the new policies make sense.

Bruce Bergen, freeholder chairman in the County of Union, said the new policies make sense.

“The issue of money should not be the get-out-of-jail-free card,” said Mr. Bergen, a Democrat.

But he also said they have come with a heavy financial burden.

Mr. Bergen said the county’s 2016 budget includes $1.8 million to implement required changes, which is 18% of last year’s tax increase. That includes hiring 11 new prosecutors and 18 new sheriffs.

Atlantic County Executive Dennis Levinson said the revisions would cost his county $2.5 million. Prosecutors had requested 10 new assistant district attorneys and four staff members, and the sheriff asked for seven more officers. The new rules were unnecessary, he said, noting his county had already reduced its jail population.

“We’re going to have to raise taxes or cut services,” said Mr. Levinson, a Republican. “How else?”

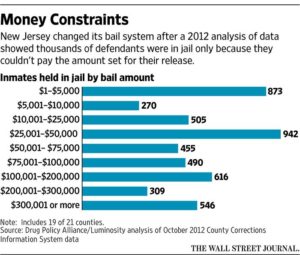

The state’s changes were partially prompted by a 2013 report issued by criminal-justice consulting firm Luminosity and advocacy-group the Drug Policy Alliance. The report showed 73% of New Jersey jail inmates were awaiting trial, and 39% of all inmates had the option to pay bail but remained in jail.

The average defendant awaiting trial had spent 10 months in jail, it showed.

Several counties have been designated pilot programs. Earlier this week in a Passaic County courtroom in Paterson, N.J., inmates at a jail several blocks away appeared in rapid succession on a flat-screen TV. The inmates, whose charges included distributing bath salts, heroin and drug possession, had been arrested less than 24 hours before.

Previously, these hearings were held at 16 municipal courts.

Passaic County Prosecutor Camelia M. Valdes, who praised the changes, said her office of 50 prosecutors has been scrambling to put in place new pretrial procedures and adjust to new technology.

“It’s scary when whole systems change like this,” said Ms. Valdes. “This is the biggest sea change I’ve seen in New Jersey criminal justice.”

Write to Corinne Ramey at Corinne.Ramey@wsj.com